Interview: A new book on venture capital's impact on workers, with Catherine Bracy

"World Eaters" argues that many of the problems raised by tech industrialization can be traced to venture capital's push for grandiose returns.

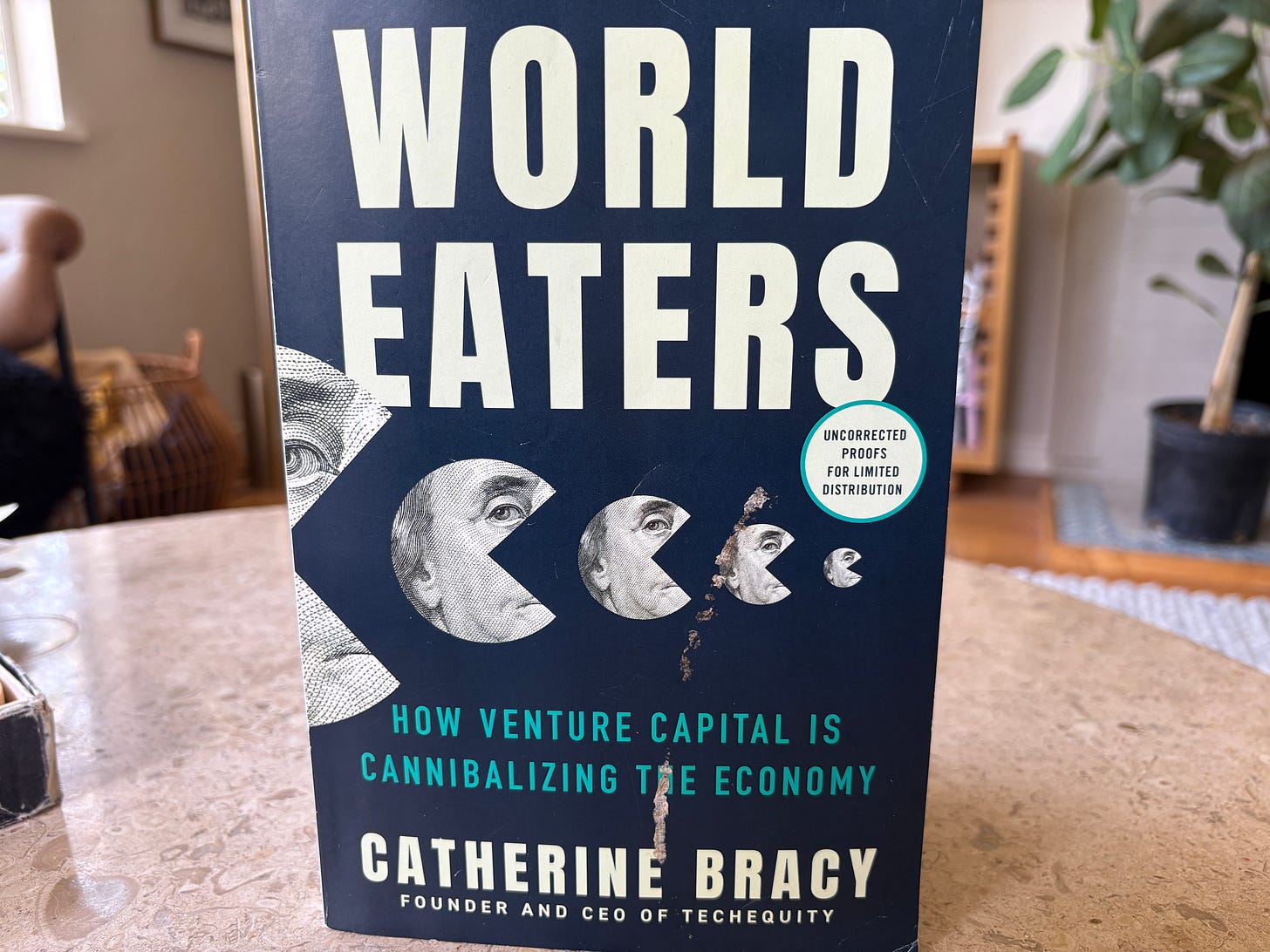

Follow the money. That’s a time-honed rule for journalists, investigators and anyone who wants to get to the root of a political or economic story. Catherine Bracy, a Bay Area technologist and founder of the TechEquity advocacy group, used that idea as the premise of her new book, World Eaters: How Venture Capital Is Cannibalizing the Economy.

Bracy argues that amid all the outcry about tech and inequality the last decade or so, venture capital funding — the fuel behind the industry — has gone conspicuously underanalyzed. And many of the questions about the societal expense exacted by some of these companies can be traced to venture capital’s emphasis on mega-returns, a function of what’s called the Power Law.

I spoke with Bracy this week about what the push for endless growth has meant for the world of work — from gig platforms, to Silicon Valley’s reliance on contractors, and more. A condensed version of our chat is below. As a brief note of transparency, The Worker Agency, which produces this newsletter, did help promote Bracy’s book but had no role in selecting this topic today.

ER: World Eaters has a breakout section on labor. Why did you choose to highlight employment issues?

CB: It happens to be one area where tech is having an outsized influence. It was important for me to draw the direct line from the struggles that everyday people are having on the ground to tech and even further upstream to venture capital.

Ad: Hush Line is a platform that provides individuals and organizations with open-source, end-to-end encrypted, anonymous tip lines.

You’ve worked in the industry for more than two decades — how would you sum up the way tech companies and venture capital firms view workers?

Reid Hoffman wrote a methodology of venture capital called Blitzscaling in which he refers to workers as “growth limiters.” That really jumped out to me when I read it. It made explicit something that we were feeling as advocates for a while, which was that unlike previous economic eras where workers were really seen as assets of a company, in the tech economy and the worldview of venture capitalists, they were viewed as a sort of a necessary evil. The goal has been to reduce workers to the lowest number possible.

The labor chapter focuses in part on gig work, how companies like Uber have tried to skirt labor regulations by pitching themselves as marketplaces not employers. It’s interesting to see the hype — and concerns — about gig work have now largely been replaced by AI. Do you think the question of gig work, whether it is just a fancy costume for worker misclassification, remains an important one for the country to sort out?

Gig work is one prominent way in which work has been compartmentalized by tech — fractured, offshored, and outsourced. And it has eroded worker power and the ability to organize, and, in some cases, for human dignity to exist at work. I'll say if I were writing this chapter now, it would be more focused on the way that AI is impacting workers.

There's apparently a group chat with a bunch of AI and CEO/investor types where they are taking bets on when the first zero-employee company will become a unicorn [a startup valued at more than $1 billion]. And so now they’re oriented around this world in which employees don't exist. So yeah, I think that they're actively hostile.

It’s interesting that Blitzscaling author Reid Hoffman is considered part of tech’s left flank these days. Obviously much of tech leadership class has drifted significantly to the right. And we’re increasingly seeing an idea about work become fetishized — a Hunger Games-style, cutthroat take that you’re only as good as how remarkable you are, every minute of the day. In Silicon Valley, this is often exalted as a natural order. Do you believe this is a philosophy at its heart, or a business ploy in disguise?

With venture capitalists, it's very hard to separate the two. I keep trying to rationally game some of this stuff out, like, why would Mark Zuckerberg go with Trump? Ultimately it occurred to me that some of these things don't line up, because they’re not actually about the money. These folks have an identitarian commitment to this mode of operating.

One way they explain it, is that Biden didn't call them heroes. He didn't invite them to the meetings, and he didn't celebrate what they were doing and [former FTC Commissioner] Lina Kahn was coming after them. And so they went to Trump, who had created a space for them to be adored. The business mindset is a religion for them. And the money is just a proxy metric for how valid they are as people.

Do you think that this hostility to workers is a departure from the past?

No. One thing that I came to understand in the wake of the election is that the tech industry, and Silicon Valley venture capital in general, have been such a perfect embodiment of the neoliberal economic order. In regards to labor, there was this sense that it was a place where businesses and corporations could find cost savings or higher earnings, if they could break down unions, deregulate, or undermine labor protections.

How have your own views evolved on tech's relationship to its workforce?

When I started TechEquity, we had a sense that some companies would operate differently if they were provided an invitation or an opportunity to do things differently. But we built that invitation, and they weren't interested.

That data point shaped my thoughts, and was a big input to writing the book. [I wanted to explore why] their incentives did not align with our incentives.

You make clear that your critique in the book is largely about systems, not individuals. There is a framework in place that incentivizes people, firms, and companies to comport themselves in certain ways. How does change happen then, knowing the scale and complexity of these issues?

I don't think asking VCs to go against the financial structure they exist in is realistic. And this isn't about banning VC or even constraining VC. We need to address how the system is structured. And then could we build another system with incentives for better worker outcomes, solving real problems, and adding value that isn’t just financial value but includes financial value — creating companies that are actually good.

There are already investors doing it. And the government can play a role in catalyzing this, through an industrial policy for private capital markets. Government could say, “Ok, this is the societal outcome we want from this business practice. We are going to create incentives that we think will push people towards operating in a way that will get us to those outcomes.”

Thank you Catherine.

Here’s what else I’m reading this week:

I’m the Canadian who was detained by Ice for two weeks. It felt like I had been kidnapped (The Guardian)

US Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick tells Fox viewers to buy Tesla stock

JD Vance spoke at a summit hosted by VC firm Andreessen Horowitz that revolved in part around the PLIGHT OF WORKERS. He dismissed employment concerns about AI and spoke about what he called the “alleged tension between the populists and the techno-optimists,” in part over labor, and continued to tout what he said will be a rebirth in manufacturing in the US. It’s still interesting to me to hear Republicans like Vance rail against “cheap labor” and globalization, and exalt workers in this way.

The ABUNDANCE THEORY is here and will be all over the place for the foreseeable future. Here is co-author Derek Thompson in The Atlantic with an overview of the pitch and a leftist critique from Malcolm Harris in The Baffler.

Morgan Stanley Went Big on DEI, and No One Is Happy About It (WSJ)

A Yale analysis of POTENTIAL TAX CUTS coming in the new administration found that they “lowered rates for people of all income levels but concentrated the largest benefit among the wealthiest. Combining an extension — which would concentrate benefits among the same groups — with cuts to safety net programs would actively transfer money from low-income people to high-income earners,” according to the Washington Post.

A detailed report from Capitol Weekly about GAVIN NEWSOM’S new podcast, which, as we and many others have noted, has drawn fire for focusing on MAGA guests. @yashar has a good, Tweet-sized summary. CW said that Newsom praised or agreed with Charlie Kirk, his first guest, nearly 125 times, and that his favorability with liberals dropped from 46 to 30 percent.

More ELECTION POST-MORTEMS, this one from Eric Levitz at Vox and political consultant David Shor. NYmag summarizes the three main points: “(1) Trump made significant gains as compared to his 2020 performance among Black, Latino, Asian American, immigrant and under-30 voters; (2) Trump did better among [lesser] engaged voters than did Kamala Harris, reversing an ancient assumption that Democrats would benefit from relatively high turnout; and (3) inflation was the overriding issue among persuadable voters, even as Democrats overemphasized the threat to democracy posed by Trump’s return to power.” Also: a continued focus on Gen-Z’s rightward drift, particularly among young men. As Shor told Ezra Klein: “18-year-old men were 23 percentage points more likely to support Donald Trump than 18-year-old women, which is just completely unprecedented in American politics.”

“Sad times when an art critic can’t get sloppy at a big work party.” The New Yorker parted ways with its new art critic after complaints about his behavior at its 100th anniversary party.

YOU HEARD IT HERE FIRST. Ok, we kid. But Hasan Piker got a full spread in the New Yorker after our letter last week.

The increasingly open antisemitism and dog whistling these days is creepy and a sign of deep societal rot.

See you next week.

AD: Hush Line is a platform that provides individuals and organizations with open-source, end-to-end encrypted, anonymous tip lines.